How to Make a Screencast the Right Way

Screencasts are video recordings of a computer screen that demonstrate a specific task or process. They are excellent educational tools for teaching a wide range of subjects, from recording a PowerPoint presentation to demonstrating how to use a website or software.

Whether you’re creating a screencast for YouTube, a classroom, or an online course, these videos are one of the most effective ways to produce engaging “how-to” content.

In this article, we have reviewed the latest research and best practices on how to create high-quality screencasts, ensuring you deliver valuable content and knowledge to your audience.

What is a Screencast?

Screencasts otherwise known as ‘screen capture videos’ or ‘screen recordings’ are recordings of computer screen activity, which often contain audio narration. They are an easy way to create walk-throughs, how-to video tutorials, and other educational videos, and are widely used as a learning tool.

A screencast features various elements like text, images, and mouse movements on top of audio, allowing online instructors to present adequate learning scenarios.

Some of the subjects that can be taught through screencasts are:

Computer applications

Software demonstrations

Computer-based procedures

How to navigate a website

Step-by-step problem solving

Answers in frequently asked questions

Complex concepts

Diagrams, pictures or simulations

Recording lectures from presentations (PowerPoint, Keynote etc)

Screencasts may be the best choice, in comparison to using simple screenshots in a slide presentation if you want to accomplish any of the above tasks. Let’s see why…

What are the Benefits of Using Screencasts?

In many scientific studies concerning screencasts (eg., Palaigeorgiou, and Despotakis, 2010) learners have liked the authentic nature of screencasts and said that screencasts increased their application-specific confidence, and helped them be more confident about the knowledge provided in the lesson.

Undoubtedly, screencasts have a significant advantage since learning becomes less impersonal and creates a sense of social presence that can’t be found in traditional books.

Perhaps, the most important benefit is that they provide worked-out examples, where the learning content is featured within an authentic context.

In their study, Palaigeorgiou and Despotakis (2010) support that screencasts offer the following:

Learners develop a better mental model of human-interface interactions.

An ‘agency’ effect is created, namely, the impression of self-executing the task presented.

Initial learning is fast since students do not spend time interpreting the steps as is required for the comprehension of textual instructions.

There is an immediate example on the lesson’s subject instead of asking a student to imagine a situation, and, hence, unproductive cognitive load while skipping between different sources (e.g., from books to the computer) is circumvented.

A user learns by observing the desired behavior of an expert, and, consequently, it aids learners with low self-efficacy in exploring the demonstrated behaviors.

There are multiple benefits to using screencasts and demonstrating the lessons in this way. If you are second-guessing yourself though, you might want to consider the following advantages.

Here’s what screencasts can do for you:

Provide demonstration of complex processes

Allow self-paced learning and additional flexibility

Ensure consistent delivery of instruction to all learners

Deliver reusable content that can be played multiple times

Enhance retention and understanding of the material

Help broaden your audience reach

Offer real-time feedback

Improve personalized learning

In some cases, screencasts can also serve as valuable documentation for troubleshooting, especially in customer support, and when onboarding new employees or students to your course.

However, not all screencasts are of equal quality and educational value. This largely depends on the screencast recording tool you are using and what you can do with it. More on this later.

What are the Main Components of a Screencast?

Sugar, Brown, and Luterbach (2010) analyzed the components of screencasts and found that they mainly consist of:

A bumber: Α statement at the beginning or end of a broadcast. (e.g., “Hi, this is your instructor from…class.”)

Screen movement: The screen movement can either be static, maintaining a constant frame in which the cursor moves within that frame or dynamic when the screencast follows the cursor.

Narration: Some screencasts’ audio commentary is an explicit description of a procedure that coincides with what is displayed on the screen. This description can either be explicit or implicit.

To get an idea of this audio commentary, here are a few examples of both explicit and implicit descriptions.

Explicit description examples

Example for a Word Processor:

“Click on File in the top-left corner, then select New Document.”

“Type your document title in the header section, and press Enter.”

Example for Spreadsheet Software:

“Select cell A1 by clicking on it, then type ‘Sales Data’.”

“Click on the Formulas tab, then choose Insert Function.”

Example for Graphic Design Software:

“Click on the Rectangle Tool in the toolbar, then drag to draw a rectangle on the canvas.”

“Select the text tool, click on the canvas, and type your desired text.”

Implicit description examples

Example for a Word Processor:

“Start a new document.”

“Add a title to your page.”

Example for Spreadsheet Software:

“Enter your data in the spreadsheet.”

“Use a function to calculate the total.”

Example for Graphic Design Software:

“Draw a shape on the canvas.”

“Add some text to your design.”

The majority of screencasts include a combination of both of these narration formats. Of course, there are screencasts with no narration at all.

However, it is preferable to use narration because it can make your content more powerful, engaging, and personal. Most of the studies (eg., Ali, Samsudin, Hassan, and Sidek, 2011) agree, saying that screencasts with narration are significantly more effective than screencasts without narration in enhancing students’ learning performance.

How to Design an Effective Screencast: Best Tips for Success

Bad screencasts can hurt the learners’ satisfaction and even worse the quality of learning.

For example, screencasts are ineffective when:

They have inflexible content structures and prevent exploratory learning.

They have browsing difficulties and provide a predetermined pace of information.

They lead to a delusion of skills and are not suitable for learning advanced operations.

Is there a way to prevent these disadvantages?

Most screencasts we’ve seen provide the same experience that pushes viewers into passivity and often leads to superficial learning with learners forgetting what has been demonstrated in the first place.

Researchers in screencast design though, found that there are specific design guidelines that can be applied to provide more active video consumption.

Here is a summary of those guidelines:

1. Add interactivity to your videos

To maximize the impact of your video content, you need to allow learners to have control over the presented material. Therefore, adding interactivity that helps them become more engaged with the experience is a crucial component of screencasting design.

With interactivity, representational holding is reduced as smaller chunks of information have to be processed in the working memory (Ertelt, 2007).

How can you achieve that? Give learners control over the pace and direction of the succession of frames. For example, give them the ability to change the playback speed and also add skip forward buttons, to let users avoid certain parts of the video. While explaining difficult procedures provide pause buttons inside the video frame to give a greater sense of control.

Create a table of contents for easy content access, especially in videos with many procedural examples.

Give learners the capability to change the viewpoint or to zoom in, so that phenomena can be explored from different perspectives.

Create breaks to give the ability to have five-second pauses. This can be achieved by adding overlays summarizing the steps explained in a certain example.

Incorporate context-related pointer keywords within the video. These can be discrete action steps appearing inside the video. Make sure to use those keywords also as hypervideo links.

Add questions that will create a dialectical relationship between you and your learners.

2. Keep videos short

One of the most challenging design tasks is creating meaningful videos for lengthy processes that can’t be covered in a single video. Breaking down the content into shorter videos not only makes scripting easier but also enhances clarity and retention for the viewer.

Shorter screencasts, focus on one concept, hence reducing learners’ cognitive load as well.

So, here’s what you can do for your screencasts:

Create short videos with a clear beginning and end.

Keep videos as short as possible. A length of 15 to 60 seconds is optimal for keeping the user engaged and minimizing what needs to be remembered. For screencasts, a two-minute video is long enough to explain a specific procedure.

Alternatively, introduce physical changes on the screen or add intentional pauses – such as temporarily dimming the screen, to create distinct segments within the video.

These small adjustments can help to structure the content, guiding viewers through the material in a more organized and impactful way.

3. Craft your titles carefully

Carefully crafted titles are key to making your content easy to find and navigate. By using clear and accurate labels, you provide learners with quick access to the information they need.

Here are some tips on making this happen:

Organize your content chronologically, alphabetically, or topically.

Adopt a conversational tone in your titles to help learners draw connections between videos or screenshots.

Keep titles concise while clearly conveying the learning objective of each video.

Maintain consistency by presenting similar types of information in the same location and format across your videos. This consistency allows learners to develop a mental framework for navigating your content, making it easier for them to find and understand the material.

4. Offer illustrated tutorials at the end of your lecture

Designers should consider the “expertise reversal principle,” which suggests that screencasts effective for novices during the initial learning phase may lose their effectiveness—or even hinder recall—once learners have a foundational understanding of the material.

To help ensure that learners retain the information provided, consider the following strategies:

Use Simplified Videos: Provide videos that focus solely on a sequence of screenshots of the key actions performed, or offer a filtered view that highlights only the actions not previously covered in earlier videos.

Transition to Illustrated Tutorials: As learners develop a solid understanding of the procedures, replace detailed screencasts with illustrated tutorials. Research by Novakovic, Milic, and Milosavljevic (2013), has shown that illustrated tutorials are more effective for helping learners recall already acquired procedures during later stages.

5. Give learners practice opportunities

Practice is the key to improving the transfer and application of knowledge. The success of learning is closely tied to the amount and quality of practice. When it comes to procedural knowledge, the likelihood of forgetting how to perform tasks increases with the number of steps involved.

Encourage your learners to actively repeat the procedures demonstrated, and whenever possible, provide immediate feedback. Assign them specific tasks that require applying what they’ve learned, rather than just mechanically following the steps.

Additionally, incorporate spaced practice into your lessons, as it is one of the most well-established principles in psychology for enhancing learning. Urge learners to revisit and repeat a procedure at various points throughout the course, using task completion exercises.

This approach reinforces their understanding and builds confidence in their ability to perform the procedure independently.

6. Give knowledge-encoding opportunities

Learners seek opportunities to encode knowledge through activities that boost their confidence and help them better organize the material. To support this, consider the following strategies:

Create Post-Screencast Questionnaires: Design questionnaires to assess learners’ understanding of the content immediately after the screencast. This not only reinforces key concepts but also provides valuable feedback on their comprehension.

Offer Multiple Views of the Content: Enhance practice by providing various formats of the material, such as concise, printable summaries, e-books, or downloadable resources. These alternatives allow learners to review and engage with the content in different ways.

Incorporate Multimodal Learning: Present the material through various modes—text, audio, and video—to cater to diverse learning preferences. Different forms of organization, like mind maps or infographics, can also help learners structure their understanding more effectively, enabling them to achieve multiple study goals simultaneously.

7. Give explicit time requirements

Provide learners with a clear connection between their learning objectives and the estimated time required to achieve them. This approach encourages learners to organize their study plans effectively, helping them to schedule their study sessions for long-term success.

At the start of the course, offer a support tool that guides learners in creating personalized study plans. This tool should consider their learning objectives and the time they have available, empowering them to manage their progress and stay on track throughout the course.

8. Apply the multimedia design principles

Research on learning from multimedia indicates specific principles, which guide instructors when it comes to creating an effective multimedia message design. In the table below you can see how multimedia design principles can be applied in screencasts.

Examples are taken from Razak’s, and ALI’s (2016) study.

Principle of Signalling

Students will learn better if the signal to process the information is given.

Insert signals, highlighting or assertion of important information (key-words, pointer phrases, for students to show what to do and how to organize them.

Principle of Coherence

Students will learn better if external elements are removed.

Issuing interesting but irrelevant statements or graphics used.

Principle of Redundancy

Students will learn better if the information is not provided within the same sensory channels.

Avoid showing print text and narration simultaneously with the display screen. It’s ok to present narration simultaneously with the display screen.

Principle of Spatial Contiguity

Students will learn better if the printed text is near the graphics that corresponds to it, reducing the need for visual scanning.

Place text close to the same part of the animation.

Principle of Temporal Contiguity

Students will learn better if the narrative and animation are displayed at the same time to reduce stake memory.

Present narration and animation simultaneously rather than individually.

Principle of Signalling

Students will learn better if the signal to process the information is given.

Insert signals, highlighting or assertion of important information (key-words, pointer phrases, for students to show what to do and how to organize them.

Principle of Coherence

Students will learn better if external elements are removed.

Issuing interesting but irrelevant statements or graphics used.

Principle of Redundancy

Students will learn better if the information is not provided within the same sensory channels.

Avoid showing print text and narration simultaneously with the display screen. It’s ok to present narration simultaneously with the display screen.

Principle of Spatial Contiguity

Students will learn better if the printed text is near the graphics that corresponds to it, reducing the need for visual scanning.

Place text close to the same part of the animation.

Principle of Temporal Contiguity

Students will learn better if the narrative and animation are displayed at the same time to reduce stake memory.

Present narration and animation simultaneously rather than individually.

Other multimedia principles we have already mentioned are:

The segmenting principle (providing short chunks of information).

The worked-out example principle.

The animation and interactivity principle.

9. Make learners more active

Self-regulated learning is a growing field of educational research, which seeks how students can become more active in the learning process, by creating learning goals, inferring meanings, and applying strategies.

In self-regulated learning conditions, learners are capable of monitoring, controlling, and regulating aspects of their cognition.

Loch and McLoughlin (2011) have proposed specific guidelines, with which an instructor can foster each stage of learners’ self-regulation through screencasts:

Active Learning Dimensions

Application in screencasts

Planning and goal-setting

1) Give an overview of the concept being presented. 2) Activate prior knowledge. Remind them about what they may already know.

Monitoring processes and metacognitive control

1) Ask learners to set a goal for the session. 2) Present questions and tasks to check for understanding, and to get students to engage in the problem-solving process actively.

Reflection on self-knowledge and task achievement

1) Encourage learners to reflect on the learning process and their understanding of the concept. 2) Ask learners to document areas of uncertainty and to prepare questions for the discussion section.

Planning and goal-setting

1) Give an overview of the concept being presented. 2) Activate prior knowledge. Remind them about what they may already know.

Monitoring processes and metacognitive control

1) Ask learners to set a goal for the session. 2) Present questions and tasks to check for understanding, and to get students to engage in the problem-solving process actively.

Reflection on self-knowledge and task achievement

1) Encourage learners to reflect on the learning process and their understanding of the concept. 2) Ask learners to document areas of uncertainty and to prepare questions for the discussion section.

10. Take care of the narrative you develop

To keep your learners engaged, avoid the monotony of a single voice throughout your content. Relying on just one presenter can make demonstrations feel repetitive and dull. Instead, incorporate a variety of presenters with different styles and perspectives. This diversity maintains interest and enriches the learning experience by offering multiple viewpoints.

💁 Your Instructional Video Style: How to Craft the Perfect Learning Experience

When presenting, aim for simplicity and clarity as well. Speak directly and conversationally, using an active voice and positive statements. Keeping your sentences straightforward and easy to follow will help massively.

On top of this, focus on providing procedural information rather than conceptual details. Learners typically watch “how-to” videos to understand the specific steps needed to complete a task.

So, your video should guide them through the process, enabling them to achieve the task quickly and effectively. Introduce conceptual information only when it is essential for understanding the procedure at hand.

7 Steps for an Effective Instructional Screencast Design

Now that we’ve seen the most popular design guidelines for screencast production, let me help you apply them to create your screencast by following seven simple steps.

Whether you are creating this screencast to showcase in a classroom, use it as part of an online course, educate your customers, or simply create a YouTube video, this is how it’s done.

Step 1: Study others

Begin by watching a variety of screencasts created by others. Observing both well-executed and poorly-designed examples will provide valuable insights into what works and what doesn’t.

This analysis can help you identify best practices and common pitfalls, which can inform the design of your own screencasts.

As you study these examples, consider the following:

Content Organization: How is the information structured? Is the flow logical and easy to follow?

Visual and Audio Quality: Are the visuals clear and engaging? Is the audio crisp and free of distractions?

Interactivity: Does the screencast include interactive elements that engage the viewer? If so, how effective are they?

Pacing: Is the pace appropriate for the content? Does the screencast move too quickly or too slowly?

User Engagement: How does the screencast keep viewers engaged? Does it use storytelling, questions, or prompts to maintain interest?

By critically evaluating these aspects, you can develop a clearer vision of what makes a screencast effective and apply these lessons to your work.

Step 2: Prepare Thoroughly

Invest time in your preparation to make sure you have all the resources and equipment you need. First and foremost, focus all your efforts on finding a high-quality screencast tool.

Best Screencast Software to Choose From

There are many screen recording software in the market that can help you create screencasts. You can choose based on your budget (free, paid, premium) or the functionality and features you need.

Here are a few examples:

Screencast-o-matic

Camtasia

Filmora SCRN

Apple QuickTime Player

Screenr

PowerPoint even has its own recording function helping you turn your to make your PowerPoint presentations into screencasts. Find out how here.

Other tools like Loom and Nimbus are handy as well, especially if you are using Google Chrome because they are available as Chrome extensions.

Choose the tool that works best for you, and always edit the result. You may opt-in for the software that also serves as a video editing tool or connects with a video editor to speed up the process.

💁 Check out our list of the 36 best training video software here.

💡LearnWorlds’ interactive video player can help you add interactivity to your screencasts. You can add annotations, pop-ups, clickable buttons, questions, watermarks, table of contents, subtitles, or even show interactive transcriptions extracted automatically from your videos!

Other Tools to Consider

What’s great about screencasts is that they don’t require much equipment to begin with. A computer – either a Windows PC or an Apple Mac that connects with your chosen screencast video software, and an optional webcam will do the trick.

However, you want your screencasts to have top audio quality and eliminate background noise as much as possible to avoid distractions. Investing in a good microphone can make a difference here, and the good news is that you don’t need to buy an expensive one.

Instead of relying on your computer’s internal microphone, get headphones with a built-in microphone and you are good to go.

Step 3: Plan your content

Planning the content for your screencast includes three main subjects: a) What you want to achieve through your screencasts, b) how you will narrate your demonstrations, and c) what interactivity features you are going to use.

The questions below will help you understand these three elements:

What are your learning goals and content?

Create a clear plan with your learning goals and objectives.

How will you achieve those objectives through your screencasts?

What will your script/narration be for each screencast?

Create clear and concise story scripts or storyboards for the screencasts that are going to be recorded.

Which will your bumper be?

How many narrators will you have?

Will you appear in the video?

How explicit or implicit will the script be?

How will your mouse movement be?

What practical examples will you include in your description?

How will you help relate tasks between videos?

What kind of questions or statements are you going to use to make learners more active? (see the table about active learning)

What interactivity features will you add to each video?

Will you give learners a table of contents?

Will you give learners the capability to change the video’s viewpoint?

Will you insert questions inside the video?

Where will you insert breaks, pointer phrases, and highlights?

If you are a novice screencast creator you may need a few hours to create your first screencast, but this time should reduce significantly with experience.

Step 4: Start recording

Once you are ready, you can record your screencast. Choose whether you want to record your entire screen (full desktop), a specific browser tab, or your webcam.

Before you hit the ‘Record’ button, configure your system audio and do a test run to see if your video and audio are working properly. If you are planning to use any drawing tools have them ready as well.

Preferably, record audio during screen capturing. In case you are not giving out any voiceover instructions, add some music to play along in the background.

During the recording, your mouse movements should be slower than usual when something is being pointed out. These need to be controlled to avoid becoming annoying and distracting to the viewer.

If an error occurs in a sentence, sometimes it is better to pause and repeat the entire sentence without stopping the recording and edit later (cut out the bad parts) than restart the recording from the beginning (Mohorovičić, 2012).

Step 5: Edit your screencast video

As previously mentioned, a screen recorder with a built-in video editor can help you easily edit videos. With it, you can add the interactive elements you want, craft your titles carefully, and apply segmentation wherever needed.

You can also choose to cut parts of your video to make your screen capture as professional as it can be e.g. to correct a mistake you made or to remove any app notifications that might have popped up on screen during the recording.

Remember to create videos that last no longer than two minutes. Otherwise, make sure to create intentional and meaningful pauses in between segments.

Step 6: Save and share your screencast

Once editing is done, make sure you save your finished screencast. That is to not risk losing it after putting so much effort into creating it.

Most screencast tools will allow you to share your screencast via email or upload it to your Google Drive, which is great. Once you are ready to show it to your audience, you can choose to upload it on Vimeo or YouTube or embed the video file in your course content right away.

Step 7: Offer assistive learning material

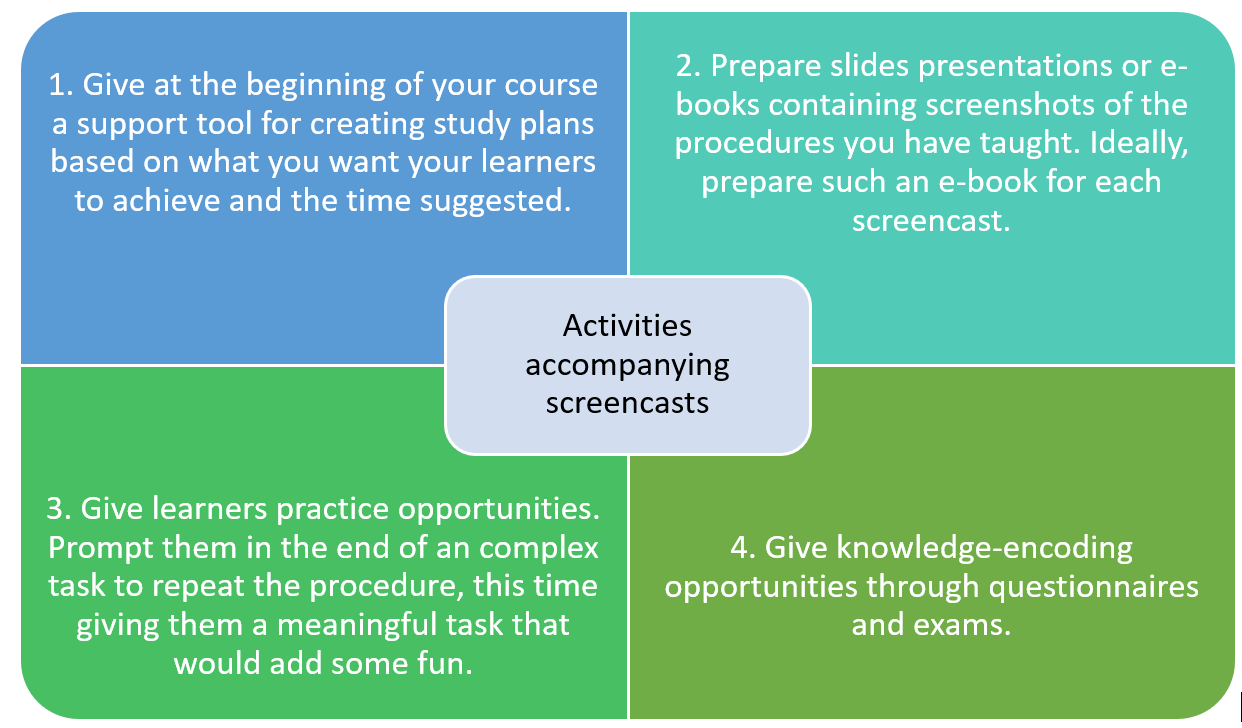

Finally, if you want your screencast to perform well, you have to accompany it with meaningful activities that will boost your video’s effectiveness.

Here are some activities that you can make use of to accompany your screencast:

Activity #1: Personalized learning plans

At the beginning of your course offer a support tool for creating study plans based on what you want your learners to achieve and the time suggested.

Activity #2: Create presentations and e-books

Prepare slide presentations or e-books containing screenshots of the procedures you have taught. Ideally, prepare such an e-book for reach screencast.

Activity #3: Offer repeating and meaningful tasks

Give learners practice opportunities. Prompt them at the end of a complex task to repeat the procedure, this time giving them a meaningful task that would add some fun to the process.

Activity #4: Try questionaries and exams

Offer knowledge-encoding opportunities through questionnaires and exams to allow learners to test their knowledge evaluating what they’ve learned so far.

Ready to Use Screencasts to Educate Your Learners?

With all this preparation, you can be confident that your screencasts will have the greatest impact on your learners!

By following these steps, you’ll effectively reduce cognitive load and transform your videos into concise, digestible bits of information that boost engagement and participation.

Remember to continually reflect on your work, gather feedback from your learners, and refine your screencasts with each iteration!

Want to learn more? Find more information on how to create educational videos in the LearnWorlds Academy’s course Video-Based Learning (free course).

Research on Screencasts & Further Study

[1] Loch, B., & McLoughlin, C. (2011). An instructional design model for screencasting: Engaging students in self-regulated learning. [2] Novakovic, D. R. A. G. O. L. J. U. B., Milic, N., & Milosavljevic, B. (2013). Animated vs. illustrated software tutorials: Screencasts for acquisition and screenshots for recalling. International Journal of Engineering Education, 29(4), 1013-1023. [3] Mohorovičić, S. (2012, May). Creation and use of screencasts in higher education. In MIPRO, 2012 Proceedings of the 35th International Convention (pp. 1293-1298). IEEE. [4] Oehrli, J. A., Piacentine, J., Peters, A., & Nanamaker, B. (2011, March). Do screencasts really work? Assessing student learning through instructional screencasts. In ACRL 2011 Conference Proceedings (Vol. 30, pp. 127-44). Philadelphia: Chandos. [5] Ali, A. Z. M., Samsudin, K., Hassan, M., & Sidek, S. F. (2011). Does screencast teaching software application needs narration for effective learning?. TOJET: The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 10(3). [6] van der Meij, H., & van der Meij, J. (2013). Eight guidelines for the design of instructional videos for software training. Technical communication, 60(3), 205-228. [7] Despotakis, T. C., Palaigeorgiou, G. E., & Tsoukalas, I. A. (2007). Students’ attitudes towards animated demonstrations as computer learning tools. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 10(1). [8] Plaisant, C., & Shneiderman, B. (2005, September). Show me! Guidelines for producing recorded demonstrations. In Visual Languages and Human-Centric Computing, 2005 IEEE Symposium on (pp. 171-178). IEEE. [9]Ertelt, A. (2007). On-screen videos as an effective learning tool. The Effect of Instructional Design Variants and Practice on Learning Achievements, Retention, Transfer and Motivation. Dissertationsschrift, Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg. [10] Palaigeorgiou, G., & Despotakis, T. (2010). Known and unknown weaknesses in software animated demonstrations (screencasts): A study in self-paced learning settings. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 9, 81-98. [11] RAZAK, M. R. A., & ALI, A. Z. M. (2016). Instructional Screencast: A Research Conceptual Framework. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 17(2). [12] Sugar, W., Brown, A., & Luterbach, K. (2010). Examining the anatomy of a screencast: Uncovering common elements and instructional strategies. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 11(3), 1-20.(Visited 9,365 times, 1 visits today)

Course Designer & Content Creator at LearnWorlds

Anthea is a Course designer and Content Creator for the LearnWorlds team. She holds years of experience in instructional design and teaching. With a Master of Education (M.Ed.) focused in Modern Teaching Methods & ICT (Information & Communications Technology), she supplements her knowledge with practical experience in E-Learning and Educational Technology.

Kyriaki is a Content Creator for the LearnWorlds team writing about marketing and e-learning, helping course creators on their journey to create, market, and sell their online courses. Equipped with a degree in Career Guidance, she has a strong background in education management and career success. In her free time, she gets crafty and musical.