US Coup Reveals How Journalism Contributed to 1898 Wilmington Massacre

Stop us if this scenario sounds familiar: a closely watched election; voters are divided along party – and racial – lines; disinformation spread in the form of journalism; and an undercurrent of violence that intensifies as voters go to the polls.

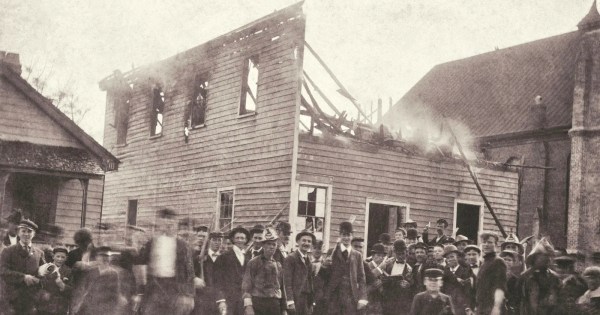

This may sound like the presidential election cycle Americans just experienced, but those same events took place over 126 years ago in Wilmington, North Carolina. As we stand on the cusp of a peaceful transfer of power from the president Joe Biden to the president-elect Donald Trump In the present day, the events of 1898 culminated in one of America’s most notorious racial massacres and the country’s first – and so far only – successful coup d’état.

That’s the subject of the new American Experience documentary, American Coup: Wilmington 1898, now streaming. on most PBS platforms. Directed by Brad Lichtenstein And Yoruba Richenthe film reconstructs the series of events that culminated in the overthrow by a group of white supremacists of North Carolina’s legally elected biracial government.

And local newspapers played a key role in bringing about the coup. Josephus Danielseditor of Raleigh’s News and Observer, was among the conspirators and used the pages of his newspaper to fan the embers of white grievance.

“It’s amazing to see the disinformation and misinformation that perpetuated the events of 1898, and how partisan those newspapers were,” said Richen, an associate professor at the University of Washington. CUNY Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism— tells TVNewser about how journalism worked in 19th century America. “Daniels was a partisan Democrat and that was the mission of his newspaper.” (At this time, the Democratic Party fiercely opposed Reconstruction and other attempts to reduce racial inequality in post-Civil War America.)

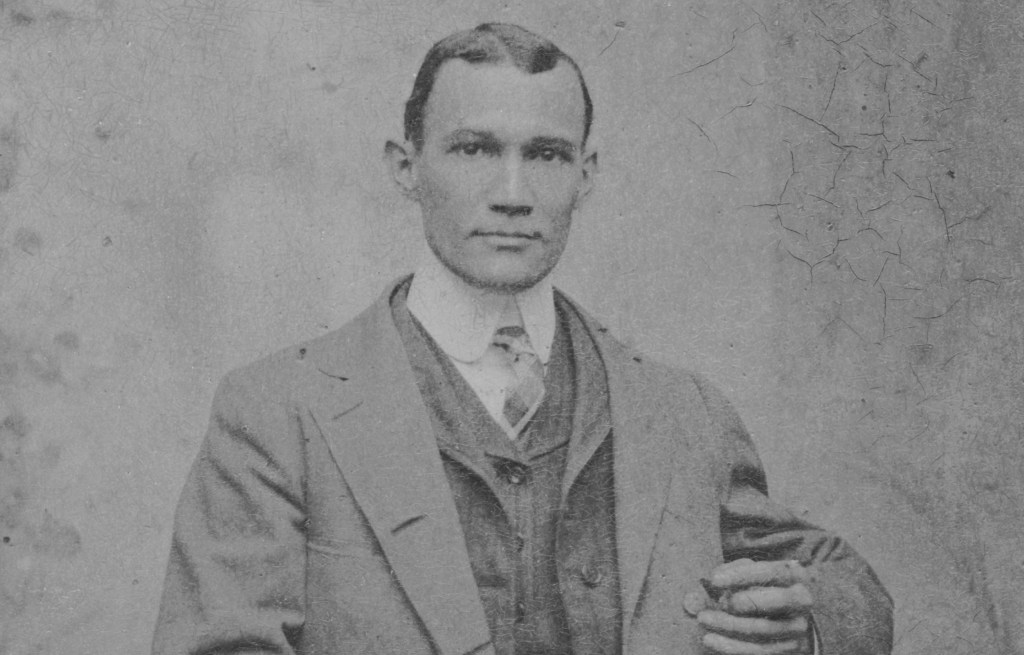

But American Coup also highlights the voices in the press who have attempted to oppose the not-so-hidden agendas of white supremacists. Black Editor Alex Viril owned and edited Wilmington’s Daily Record newspaper and dealt directly with the false allegations in a historic editorial which exposed the hypocrisy surrounding dominant attitudes in white society toward interracial coupling.

“It’s something that black newspapers have been doing across the country to report on what’s happening in communities and counter misinformation,” says Richen, linking it to the lack of local media that exists today. today. “We must continue to support local news: the majority of counties today do not have local news outlets. »

We spoke with the American Coup filmmaking team about how the past seen in their film influences our present and their feelings about the current and future state of journalism.

The American directors of Coup d’Etat, Brad Lichtenstein and Yoruba RichenCourtesy of Brad Lichtenstein/Luke Ratray

The American directors of Coup d’Etat, Brad Lichtenstein and Yoruba RichenCourtesy of Brad Lichtenstein/Luke Ratray

It’s always interesting to me how the HBO series Watchmen helped bring the Tulsa Massacre into the pop culture consciousness. Could your film be a step in this process leading to the Wilmington massacre?

Rich : We were not asked this question! You know, I think all of these things build on each other. Watchmen was an HBO series with famous characters and all that, so it’s a bit of a different beast. But there was a independent film about Wilmington which came out a few years ago, that’s when I first heard about it. SO David Zucchino’s book won the Pultizer Prize in 2021, and now there’s this movie. Hopefully, Wilmington will continue to rise into the public consciousness in the same way that Tulsa has. These events of racial terror must be part of our history.

Liechtenstein: I want to add that Yoruba is a very good actress, so if a series happens, I think she should be a part of it. [Laughs]

We’ve seen a concerted attempt in conservative circles to dismiss the kind of historical reckoning your film treats as “too woke.” The Wilmington residents you interview in the film don’t seem to feel that way, however. What is the difference between this broader message and what you have seen on the ground?

Liechtenstein: One of the things that happens time and time again in American history is that America tries to write a narrative that puts itself in the position of becoming that shining beacon on the hill. The desire to look at ourselves honestly is relegated in favor of this exceptional story. Wilmington is a great example of a history that was deliberately buried for so long. When we spoke to white descendants, many of them told us they never really knew what happened or were told anything other than the truth. We will never be the country we are trying to be if we do not reckon with and take responsibility for our past.

Rich : What I discovered in making these kinds of films is that people are hungry to be woke. And that’s what gives me hope, frankly. So whenever I hear that phrase “I woke up,” I always feel like we have to respond to that with, “Do you want to go to sleep?”

How did you divide up the interviews for the film?

Liechtenstein: One of the benefits of being a black and white filmmaking team is that the interviewees may feel more comfortable. [with one of us]we are able to accommodate them. But the Yoruba and I also have a transparent division of labor: some things tended to fall under my purview, and others, his. I think she’s interviewed more scholars than I have, and I’ve interviewed more descendants than she has. And it also partly depended on our schedule and whether we trusted each other.

Rich : I will say that Brad has definitely taken on the task of reaching out to white descendants. And that makes sense, because it was a sensitive subject. We had people who were willing to talk and others who wanted no part of it. I wasn’t really hopeful about how many white descendants we could possibly have, and I’m really grateful to those who participated. It’s not easy, but it’s so necessary.

Alex Manly was the black owner and editor of Wilmington’s Daily Record newspaper.Courtesy of East Carolina University, Joyner Library Special Collections

Alex Manly was the black owner and editor of Wilmington’s Daily Record newspaper.Courtesy of East Carolina University, Joyner Library Special Collections

When it comes to the journalistic part of the film, newspapers of the time are in some ways similar to social media today in terms of how information was communicated. What place do you see social media in the information space currently?

Rich : Many people we know get their news from social media, and what that means is one of the things I think about with my journalism students. How can we teach them to distinguish misinformation from real news? It was worrying before the recent elections, and Donald Trump made it clear that journalists are not his best friends. This is a very worrying time. Schools need to recalibrate what this means for journalism and for students.

Liechtenstein: It’s scary because the form of social media is so short and its half-life is even shorter, but its cultural impact is amplified. This sounds like a recipe for poorly informed citizens. In the Wilmington era, newspapers had agendas that they pushed, but even the most racist and biased articles were between nine and 12 paragraphs long!

America’s Coup was made for PBS, and there are fears that public television will see its budget slashed under the new administration. Are you concerned about implementing future projects at these outlets?

Liechtenstein: I’m less worried about where my next project will be, but I think public media should always make their case within the framework of our democracy. Commercial media must pay attention to the bottom line, but public media is responsible to democracy and what a democracy demands of the people and its citizens. I know that seems like a stretch, but if you just compare Netflix’s release schedule to that of public media, you’ll see that the latter takes Americans inside communities and periods of history and asks tough questions .

Rich : And it’s free! That says it all, frankly. And yes, that’s what Brad said too. [Laughs]